Point Lobos State Park is six miles south of where I live in Monterey, California. In the mid-19th century, from about 1861 to 1882, some 250 whales were processed at Whalers Cove in Point Lobos State Park.

Whales were slaughtered primarily for lamp oil and machinery lubricant. The widespread use of cheaper kerosene and other petroleum products put most shore whalers out of business in California by 1880. Good for the whales, and even better for John D. Rockefeller who built a fortune on the nation’s desire for kerosene lamp fuel in the era before electricity. California’s own petroleum oil industry boomed in the 1890s, further reducing the value of whale hunting.

Along with Monterey, Point Lobos was one of the major shore whaling stations along the California coast until 1882. By 1874 an estimated 4,000 whales were killed and processed by shore whalers in 16 California locations from San Diego to Crescent City.

The painful side of whaling.

Unfortunately commercial whaling with larger vessels in the 20th century devastated the global whale population to a far greater extent than shore whaling ever did in the 19th century when boats rarely traveled more than ten miles from the coast.

My backpack next to whale vertebrae gives scale to big backbones.

The price whale oil fetched in the market was motivation to hunt whales in the 19th century. Petroleum production saved California coastal mammals like whales and elephant seals from being slaughtered to extirpation for their blubber oil.

Whale oil barrels in Whaling Station Museum, Point Lobos State Park.

An adult gray whale yielded about 25 to 35 barrels of whale oil. The average barrel held 31.5 gallons. This meant about 750 to 1,100 gallons of oil was processed from each gray whale. The whalers at Point Lobos Station probably caught and processed 10 to 25 whales per year based on the records for a shore station 85 miles south at San Simeon operating in the same era.

Whale processing tools. The two lowest blades are blubber knives. The process of stripping the whale of skin and blubber was known as flensing.

Captain C. M. Scammon wrote one of the earliest accounts of California’s whaling history in his book Marine Mammals of the Northwestern Coast (1874). According to his data, the gray whales caught in California were estimated to have produced 75,600 barrels of whale oil by 1874 out of nearly 100,000 barrels produced at the time of writing. Scammon wrote gray whales accounted for more than 75% of the whale oil processed on the west coast after the California Gold Rush. At an average 30 gallons per whale, about 2,500 gray whales were likely processed by shore whalers along the California coast in this time period of the 19th century.

Fin whale skeleton graveyard beside Whalers Cabin, Point Lobos.

Large pots were used to boil whale blubber into oil.

The old days of whaling meant a signal person watched for whale spouts from a high point of land on the coast. Flag signals could direct boats to whale locations. Crews usually operated in two boats in case one was sunk by a whale, which was a real possibility with injured whales larger than the boats. Shore whalers often lost up to half the whales harpooned in a season. Records indicate many whales eventually captured from 1854 to 1880 showed scars of previous hunts in a year-after-year battle to avoid death from whalers during their Pacific Ocean migration.

Whale ribs beside cypress ribs.

There she blows

One good piece of news is environmental group Greenpeace states Pacific gray whales are the one species to recover from commercial whaling in the East Pacific. Gray whale numbers in 2012 are about 20,000 to 22,000. East Pacific is where the California coast is located. However, the West Pacific gray whale off Asia has an extremely small population and numbers only about 120 whales. Greenpeace states this is the most endangered whale species globally.

I came across a historical record on California whaling by a Stanford academic written in 1922. He spent time in 1921 at Moss Landing experiencing whaling at the commercial whaling station.

A History of California Shore Whaling (1922) – Edwin C. Starks, Stanford University.

Whales in Decreasing Numbers

People whose interest is in the profit of whaling often speak of the whale supply as being inexhaustible, but to appreciate that the whales are becoming scarce on our coast one has to remember back only ten or fifteen years, when standing on the shore of the open ocean and looking seaward one could nearly always see a whale or two spouting. Nowadays it is only at long intervals that a whale is seen.

Going further back, one who knew the coast forty or fifty years ago, or who has read the old books, knows that it was no uncommon sight to see a dozen or more whales at one time. In “Sketches of Life in the Golden State,” Col. A. S. Evens, 1873, writing of the coast between Halfmoon Bay and Pescadero, says: “From one height I counted not less than fifteen whales spouting at intervals.” In “The Golden State,” R. Guy McClellan, 1876, in speaking of whales, says: “hundreds of them can be seen spouting and blowing along the entire coast.” Mr. C. H. Townsend (Bulletin of the United States Fish Commission, 1886, p. 348) says: “At the San Simeon station in December, 1885, I could see whales blowing almost every hour during the day.”

Smythe’s History of San Diego states that in the early forties San Diego Bay was a favorite place for the female whales in the calving season, and at such times on any bright day, scores of them could be seen spouting. As late as 1872 fifteen whales at one time are reported to have been seen in the bay.

In the old shore whaling days the boats cruised within ten miles or so of the station. If the modern whale boat kept within this limit it is doubtful whether it would get more than a whale of two in a year. Now a considerable number of the whales are towed into the station from a distance of a hundred miles or more.

The International Whaling Commission has global whale population estimates on its IWC website. Greenpeace disputes several of the IWC estimates as being too high.

Whalers Cabin and the Whaling Station Museum

Whalers Cabin was built in 1851 by Chinese immigrants who settled on the cove. By 1862 Portuguese fishermen, primarily from the Azores, settled at Point Lobos and started the whaling station that operated until 1882.

Point Lobos State Park is an area that has seen a quarry, cannery, whaling station, coal transportation station, cattle grazing fields, real estate development project and is now mostly a wild space that has been allowed to redevelop naturally over the past 80 years.

In 1933 the land of Point Lobos was purchased by the state of California, primarily with the assistance of the Save the Redwoods League in an effort to preserve the Monterey Cypress tree in its natural environment, one of only two locations including Cypress Point, Pebble Beach where the tree is native.

Monterey Cypress on Whalers Knoll Trail, Point Lobos State Park. Allan Cypress Grove in background is largest remaining Monterey Cypress grove on the western edge of the park peninsula.

Whalers Cove 2013. At least a dozen harbor seals were basking on these rocks in the cove. This area was the site of the coal transport chute for loading ships in the 1870s.

Note the tree roots in the wall of Whalers Cabin. These are the roots from a Monterey Cypress tree planted outside the Whalers Cabin after its initial 1851 construction. Parts of the wall were removed from the cabin to preserve the growth of the cypress tree.

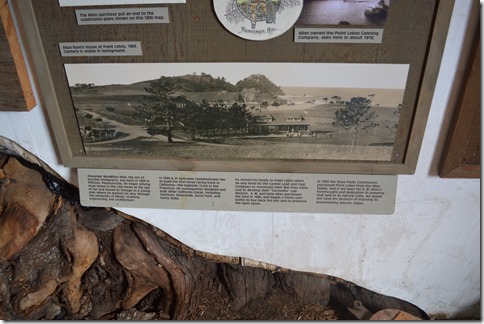

The photo shows Whalers Cove 1905 after the area became the Allan Ranch. Alexander Allan was commissioned by Claus Spreckels to build California’s historic horse racetracks like Santa Anita. Spreckels, our local 19th-century sugar magnate made a fortune processing sugar beets in Watsonville, California in Santa Cruz County. He moved his sugar beet refinery 30 miles southeast to the town that still bears his name, Spreckels, California between Salinas and Monterey.

Allan lived with his family in the ranch house and was instrumental in placing the land of Point Lobos in the ownership of the state of California to preserve the natural beauty of this unique place.

Point Lobos was established as the first underwater reserve in the U.S. in 1960. Point Lobos State Marine Reserve was established in 2007 giving additional protection to the area.

Point Lobos State Park view from Whalers Cove across Carmel Bay to Pebble Beach.

Google Maps Monterey Peninsula

Google Maps Satellite of Monterey Bay, California. San Francisco is at top of map.

Link:

http://www.pointlobos.org/history/history-point-lobos

Whale Watching in Monterey

Gray whales are still the most commonly seen whale species around Monterey Bay during the seasonal migration south from Alaska to Baja for calving in warm waters in winter, followed by the trip back north in the spring. Peak whale watching season is mid-December to late-April. the prime time to see gray whales along the California central coast. Often, the only indication of a whale is a whale spout seen as mist rising 10 to 20 feet over the ocean surface a half-mile or more from the shoreline. Seeing a whale spout and, if you are lucky, part of the back or whale fluke is a good whale sighting from shore.

Monterey and Moss Landing offer whale watching cruises year-round and that is the best way to really see whales. Humpback whales are another common sighting and Monterey is one of the best places in the world to sight a Blue Whale, the largest animal on earth and with a population around 2,500 whales along the northeastern Pacific.

Ric Garrido, writer and content owner of Loyalty Traveler, shares news and views on hotels, hotel loyalty programs and vacation destinations for frequent guests.

You can follow Loyalty Traveler on Twitter and Facebook and RSS feed or subscribe to a daily email newsletter on the upper left side of this page.