One of the common features I have seen in many American cities over the past few decades is urban renewal through reconstruction of 19th and 20th century buildings designed for the industrial age into public residential and commercial places and spaces designed for the needs of the new millennium.

My home town of Monterey, California provides a fine example of urban renewal on a small scale for a city with a population of 30,000. Monterey was called the ‘sardine capital of the world’ for a couple of decades from the 1920s to 1940s. John Steinbeck made the industrial waterfront of Monterey world-famous through his 1945 novel Cannery Row. The City of Monterey even changed the road name in 1958 from Ocean View Avenue to Cannery Row along the one mile stretch of road where the canneries stood.

The sardines dwindled from Monterey Bay after about 50 years of heavy fishing and the last cannery in Monterey closed in 1973. When I was a teenager in the late 1970s, Cannery Row was somewhat of an eyesore with several abandoned cannery warehouses blocking the scenic ocean views along the coastline. In the 1980s Cannery Row was revitalized with the construction of the Monterey Bay Aquarium on the west end and the Monterey Plaza Hotel on the east end. The railroad tracks near the shoreline leading to the canneries were torn out and replaced with a paved bicycle and pedestrian path. The area now attracts millions of tourists each year who spend money in the restaurants, bars, hotels and nearly two million visitors in 2012 went to the Monterey Bay Aquarium on Cannery Row.

As an adult I have lived in several fishing villages and mill towns in California, Maine, Massachusetts and Vermont during their dying days of traditional industries of fishing, lumber and quarries. The economy suffers after the natural resources are over harvested and the canneries and mills are shuttered and abandoned. I lived in Eureka, California in the 1980s and 90s during the environmental campaign to save the remaining old-growth redwood forest from being logged. Many of the lumber mills shut down in the past decade. In a global economy, manufacturing industries move to places of lower cost labor. Many of the industrial structures left behind are frequently near the most desirable locations for scenic views of rivers, lakes, and seashore. Waterfront locations provided resources for industry. In our time, waterfront locations generally provide the most desirable scenery for recreational use by residents and tourists.

My first visit to Detroit last month gave me the impression that city will live in urban decay for many years. Toronto, where I spent time last June, is a city undergoing one of the greatest urban renewal transformations of any city in the world as its former highly industrial waterfront on Lake Ontario is redesigned to a setting of residential housing, parklands and cultural entertainment facilities.

Minneapolis definitely has closer comparisons to Toronto than Detroit in transforming its former riverfront industrial zone of flour mills.

Minneapolis Down by the River, Then and Now

A week ago, the place name St. Anthony Falls would have drawn a blank reference for me. Minneapolis was built at the site of the only waterfalls on the entire length of the Mississippi River. The industrial age of England, Europe and the USA in the 1800s initially developed through the use of falling water as a power source for turbines to run machinery.

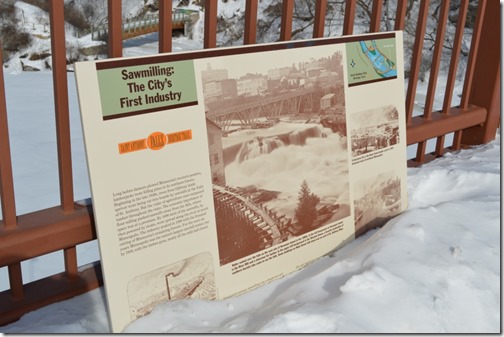

Photo of St. Anthony Falls in 1860. Board sitting in snow on Stone Arch Bridge over the Mississippi River, Minneapolis.

The power of the Mississippi River dropping 20 or so feet over falls attracted entrepreneurs and industrialists to the area who harnessed the water power to operate mills. Initially, the large mills of Minneapolis processed timber.

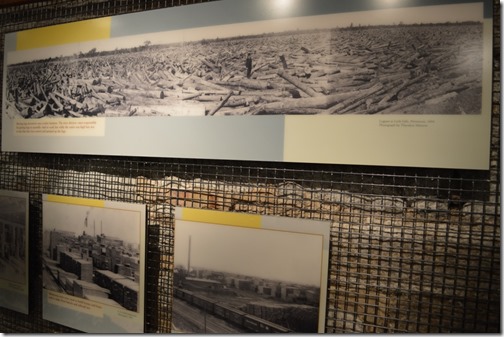

Mill City Museum display of Minnesota logging and mill industry.

Following the Civil War, logging in Minnesota went into high gear after the forest resources in the east could not meet demands of the rapidly growing nation. Minnesota was a land of extensive old-growth white pine forest, where numerous waterways followed by logging railroads made transportation of timber to commercial markets economically feasible. The lumber mills of Minneapolis reached peak production in 1899 when the city was the timber capital of the world producing over 600 million board feet of lumber. By 1919 the last sawmill in Minneapolis closed. Source: Minnesota Department of Natural Resources.

In 1837 there were 2.5 million acres of old growth white pine forest in Minnesota’s total forest lands of 27.1 million acres. In 1990, U.S. Forest Service estimated about 67,000 acres of white pines remained in the state with very little old growth trees among the 16.7 million acres of forest in Minnesota.

After the forests were extensively logged in the area, the primary industry of Minneapolis changed from processing lumber to processing the wheat crops grown on farms in Minnesota and the Dakotas. Minneapolis became known as ‘Mill City’ and the world’s largest producer of flour.

Mill City Museum is located in the former Washburn ‘A’ flour mill which at one time was the largest and most technologically advanced flour mill in the world. The original mill built in 1874 exploded from combustible flour dust in 1878, completely leveling the mill and a couple of adjacent mills. The explosion and fire killed 18 workers. In an instant Minneapolis lost one-third of its milling capacity. The mill was rebuilt and reopened in 1880 with the technological safety advancement of dust collectors.

Flour dust collector from 1883, Mill City Museum.

The mill remained in operation until 1965 when it closed down.

One of the fascinating exhibits in Mill City Museum are photos and writings from a person who was one of the squatters living in the abandoned mill in the 1980s.

Mill City Museum exhibit.

Yes, that is a giant hole in the floor. We had to watch out for it all the time and had many close calls. We tried to cover it with pallets but they kept sliding. My friend’s dog fell through it. Since this is a grain elevator it was a LONG way down. The dog died and after that we decided to use burlap bags and straw to cover it so if any other squatters came in during the night to harm us they would fall down, too! Yeah, I know, but it was either them or me. No one ever fell through.

Mill City Museum exhibit.

A massive fire burned through the abandoned Washburn ‘A’ Mill in 1991. In 2003 the remaining structure reopened as the Mill City Museum.

The Mississippi riverfront in Minneapolis today has new residential housing and parklands. Adjacent to the Mill City Museum is the Guthrie Theater, the performing arts venue for the city. Marriott Hotels has a Renaissance and Residence Inn nearby.

West Side Mill District with Guthrie Theater (left) and Mill City Museum (right) seen from the historic Stone Arch Bridge (1880-1882) crossing the Mississippi River.

St. Anthony Falls today. The water power from this site on the Mississippi River was the vital resource in the development of the city of Minneapolis.

The city of Minneapolis hopes to double the downtown population from less than 40,000 to 70,000 over the next decade through urban renewal.

Many places in the USA are moving past the industrial age and developing into the white collar corporate and tourism era. This is the Minneapolis urban renewal I have seen.

Old Milwaukee Road Depot was the train station built in 1899. The last train service was in 1971. Since 2001, the structure holds The Depot Renaissance Minneapolis Hotel and Residence Inn Minneapolis Downtown along with a seasonal ice skating rink and water park.

*****

Ric Garrido of Monterey, California is writer and owner of Loyalty Traveler.

Loyalty Traveler shares news and views on hotels, hotel loyalty programs and vacation destinations for frequent guests.

Follow Loyalty Traveler on Twitter and Facebook and RSS feed.

3 Comments

Comments are closed.