Yesterday, August 9, 2013 there were 56 police officers injured in Belfast when over one thousand loyalists protested a republican rally to mark the introduction of internment without trial in 1971 for suspected terrorists in Northern Ireland during the Troubles.

In 1997 my travel path intersected with Northern Ireland during the last summer of the Troubles before the implementation of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement negotiated an end to nearly three decades of war.

What a Trip! July 1997 Marching Season Riots Derry, Northern Ireland

I chuckled hearing the American woman in Donegal Town ask for a bus ticket to ‘Dwar’. I had been in Ireland for a couple of weeks, long enough to learn that Doire is the Irish spelling for the town name pronounced ‘Derry’ as in Londonderry, Northern Ireland.

Buying our two bus tickets to Derry was a last minute change of plan. That Monday morning we were planning to travel southwest to County Mayo in western Ireland.

The situation was one of those times where I had to look Kelley straight in the face and ask if she was truly willing to risk traveling through a war zone. The Orange Parade march through Drumcree the day before signaled a new round of violence across Northern Ireland.

The next couple of weeks Kelley referred to me as Terrorism Tourist and told me I should wear a t-shirt with a bulls eye target and the words 1-800-CALL-CNN in case I was shot.

The Troubles

The Troubles are a complex socio-political morass Northern Ireland is still reconciling with these days.

The Parades Issue was the main reason for fighting in July 1997 when Kelley and I repeatedly crossed the border of Ireland into Northern Ireland as we toured County Donegal for a month. A last-minute decision to allow one of the most contentious parades in Northern Ireland, the Drumcree Orange Parade to proceed through a Catholic area sparked a week of countrywide violence.

In late June 1997, Secretary of State Mo Mowlam had privately decided to let the march proceed. This was later revealed in a leaked document.[16] However, in the days leading up to the march, she insisted that no decision had been made.[16] She met Taioseach Bertie Ahern, who stressed that any unilateral decision to allow the march would be ‘a mistake’. The RUC and the Northern Ireland Office replied that they would make public their decision only two or three days beforehand. Earlier, Mo Mowlam had said that any decision would be released at least six days before the march. As the parade day approached, thousands of people left Northern Ireland for fear of violence like that of July 1996.[3]

Meanwhile, the residents coalition applied for a street festival to be held the same day as the march, but this was banned by the RUC. Women from the nationalist district instead set-up a peace camp along the Garvaghy Road.[16] The Loyalist Volunteer Force (LVF) threatened to kill Catholic civilians if the march was not allowed to proceed.[16] The Ulster Unionist Party also threatened to withdraw from the Northern Ireland peace process.[17] The following day, sixty families had to be evacuated from their homes on Garvaghy Road after a loyalist bomb threat.[18]

On Sunday 6 July at 3:30am, 1500 soldiers and police[19] moved into the nationalist area in 100 armoured vehicles[20] and sealed-off all the roads.[16] This led to clashes with about 300 protesters, who begun a sit-down protest on the road. The last protesters were forcibly removed from the road by 6:33am.[2] From this point onward, all residents were prevented from leaving their housing estates and accessing the main road.[16] As residents were unable to reach the Catholic church, the local priests were forced to hold an open-air mass in front of a line of soldiers and armoured personnel carriers.[16] Some RUC officers claimed that the residents taunted them about the deaths of their two colleagues at Lurgan in June while shouting pro-IRA slogans.[21] There are allegations that Rosemary Nelson, the solicitor for the residents coalition, was verbally and physically abused by the RUC. Ronnie Flanagan, then Chief Constable of the RUC, said that the decision to allow the march was taken to avoid loyalist violence.[3] The parade marched along Garvaghy Road at noon that day. After it passed, the security forces began withdrawing from the area. A large-scale riot developed. About 40 plastic bullets were fired at rioters, and about 18 people had to be hospitalized.[16]

Wikipedia – July 1997 Drumcree Parade

Wikipedia provides a concise description of the parades issue:

Inter-communal tensions rise and violence often breaks out during the “marching season” when the Protestant Orange Order parades take place across Northern Ireland. The parades are held to commemorate William of Orange‘s victory in the Battle of the Boyne in 1690, which secured the Protestant Ascendancy and British rule in Ireland. One particular flashpoint that has caused repeated strife is the Garvaghy Road area in Portadown, where an Orange parade from Drumcree Church passes through a mainly nationalist estate off the Garvaghy Road. This parade has now been banned indefinitely, following nationalist riots against the parade, and also loyalist counter-riots against its banning. In 1995, 1996 and 1997, there were several weeks of prolonged rioting throughout Northern Ireland over the impasse at Drumcree. A number of people died in this violence, including a Catholic taxi driver, killed by the Loyalist Volunteer Force, and three (of four) nominally Catholic brothers (from a mixed-religion family) died when their house in Ballymoney was petrol-bombed.[128][129][130]

Disputes have also occurred in Belfast over parade routes along the Ormeau and Crumlin Roads. Orangemen hold that to march their “traditional route” is their civil right. Nationalists argue that, by parading through predominantly Catholic areas, the Orange Order is being unnecessarily provocative. Symbolically, the ability to either parade or to block a parade is viewed as expressing ownership of “territory” and influence over the government of Northern Ireland.

This bus is making a detour due to a bomb threat of the Derry Bridge.

The Craigavon Bridge crossing the River Foyle was the focal point for a violent week in Derry. The issue was a planned march by Protestants scheduled for the following weekend with a routing across Craigavon Bridge and into the Catholic neighborhoods around the walled city center of Derry.

Hands Across the Divide are a pair of bronze statues at the west end of Craigavon Bridge. The hands almost touch.

Derry seemed tense. Armored patrol cars rumbled along the streets. Kelley noticed the British Army military vehicles were lined with brushes on the bottom that looked to be a preventative measure against rolling a bomb under the vehicle.

I have a mental image of a soldier pointing at me with his machine gun as the patrol vehicle passed by on the street about 15 feet away.

There were only a handful of people on Bus Eireann, Ireland’s national bus line, riding the bus from Donegal to Derry. And only one passenger, an American single woman backpacker in her 20s, planned to lodge in Derry. A couple days later, after a night of violent rioting in Derry, the newspaper said there were only two tourists lodging in the city. I wondered if she was one of the two terrorism tourists hanging out after the riots.

July 1997 – Plywood replacements for smashed windows in Derry, Northern Ireland. CCTV camera remained mounted on the wall.

- Derry

On Sunday evening in Derry, thousands of people joined a protest march from the Bogside to the RUC base of Strand Road.[28] Martin McGuinness addressed the crowd, calling on nationalists elsewhere to take to the streets to demand “justice and equality” and “stand up for their rights”.[25] Although the protesters returned to the Bogside peacefully,[28] there was violence in the city center.

At Butcher Gate, there were clashes between nationalist youths and the RUC. It is claimed that the RUC fired “upwards of 1,000 plastic bullets”, many of them fired “indiscriminately” and aimed “above the waist, in direct contravention of the rules governing the use of such lethal weapons”.[29] A 16-year-old boy suffered “a fractured skull, a broken jaw, and shattered facial bones amongst other injuries” after allegedly being beaten by RUC officers. He was on life support for some time afterwards.[29] An eyewitness described seeing one man, allegedly an onlooker, being shot in the face: “The side of his face was completely torn away, and he seemed to just slump to the ground”.[29] Several others suffered serious head injuries. Nine were admitted to Altnagelvin Hospital with plastic bullet injuries. At least 30 others sought treatment at first aid houses or at Letterkenny Hospital across the border. Downtown Derry was sealed off by the RUC and the British Army, exception made of the accesses via Shipquay and Ferryquay Gates.[29]

Wikipedia: 1997 Nationalist Riots in Northern Ireland

Our lodging was 16 miles outside of Derry, Northern Ireland in the small town of Buncrana, Ireland across the border in County Donegal, Ireland.

Google Maps: Derry, Northern Ireland to Buncrana, Ireland 16 miles.

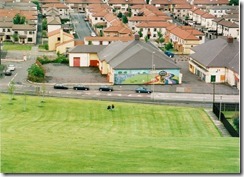

Bogside murals in the Catholic area of Derry.

Ireland had limited public transportation at the time of our visit. Train lines out of Dublin only traveled to a few locations. My often repeated saying regarding the Lough Swilly bus service for County Donegal and Derry was “You can get there, but you can’t get back again in one day.” This saying developed after learning that many routes on Lough Swilly were a one way circular direction around the peninsula, once a day.

Our lodging pattern in Ireland was three to five days in a B&B with no rental car meaning that travel to another town around County Donegal required an overnight and then catch the bus the next day on its circular pass. Hitchhiking was still fairly common in the area due to the lack of public transportation.

The Bogside. No Consent. No Parade mural in center.

The small town of Buncrana (pop. 7,200) was best known for its Fruit of the Loom textile factory in 1997. Buncrana was a victim of industrial globalization when the U.S. company moved its production facilities to Morocco in 1999 after little more than a decade in Ireland.

Castle Bridge Buncrana.

Since most tourist traffic on public transportation had to travel via Derry to reach the town of Buncrana, Kelley and I were the only guests at the B&B where we stayed the week.

We learned quite a bit about the Troubles from the perspective of the Catholic woman who owned the Buncrana B&B with her policeman husband. She was a mental wreck all week, frantic over the violence in nearby Derry.

The situation was tense in the days leading up to the Saturday Orange Parade scheduled in Derry. We arrived in Buncrana on Monday and I took a bus into Derry on Wednesday. A group of children, kids who looked to be under 10 years old, stood on a large pile of bricks beside the road and heaved stones at the Lough Swilly bus driving back across the border into County Donegal that afternoon.

In Derry I picked up a flyer announcing a sit-in on Craigavon Bridge to start Friday evening. The flyer stated something like “No weapons. Bring your toothbrush and be prepared to stay as long as it takes.”

The Catholics planned to block the bridge and prevent the Protestant Orange March from crossing the River Foyle into the Bogside.

A bloodbath on the bridge was feared.

Badgers Pub, Derry, Northern Ireland.

Bogside

The Bogside is an exclusively Nationalist and Catholic area of Derry which lies to the west of the River Foyle. Each year part of the Apprentice Boys parading tradition involves walking around the walls of the city on the Saturday nearest to the 12 August. However, the city walls overlook the Bogside and this has long been a contentious issue in Derry. In 1969 it caused what was later referred to as the ‘battle of the Bogside’. A full scale riot erupted when the Apprentice Boys jeered and taunted Catholics at the Bogside as they walked around the city walls. It was the trouble, sparked off by this, which led to the mobilisation of troops in Northern Ireland. As part of a long-term security operation the walls of the city were blocked off and the Apprentice Boys were unable to use their normal route between 1970 and 1994.

The 12 August Apprentice Boys parade is second only to the 12 July parade and is the biggest parading event in Derry. Its route along the city walls, and particularly past the Bogside, goes against the wishes of the majority of the people of the city. Over the past few years residents have come together to form the Bogside Residents Group. This group accepts that the Apprentice Boys wish to maintain their traditions, but objects to the manner in which they do so. That is, they ignore the principle of consent and apparently adopt a dismissive attitude to the rights of Nationalists. 1995 saw serious disturbances at the Apprentice Boys parades in Derry. The following year, 1996, Nationalists protested against the Apprentice Boys being allowed to walk the city walls and many people in Northern Ireland feared another Drumcree style stand-off. However, the Apprentice Boys decided to postpone the parade to “a time and a date of our choosing” and the situation passed off peacefully.

On Friday morning, sometime in the early hours after midnight, an agreement had been reached to call off the Orange Parade in Derry.

Kelly and I boarded a bus and spent a festive day in Derry drinking at the pubs and walking through the Bogside.

Derry street scene.

School kids walking to the Bogside.

Our terrorism tourism adventure had not quite ended. We passed through Newry, Northern Ireland on our way back to Dublin over the weekend. Newry is where a passenger train had been hijacked and burned out the week before.

Burned out lorry in Newry, Northern Ireland – July 1997.

Kelley and I flew from Dublin to Glasgow, Scotland for a tour of the Scottish Highlands. After a few days we were so bored staying at a coastal B&B in Ullapool that we boarded a bus to Stranraer port in Scotland to catch a passenger ferry across the Irish Sea to Belfast.

We arrived in Belfast early in the morning on July 20, 1997.

Sunday 20 July 1997

Renewed IRA Ceasefire

At 12.00pm the renewed Irish Republican Army (IRA) ceasefire began.

It [1997] was the last spell of widespread violence in Northern Ireland before the signing of the Good Friday Agreement in April 1998. The RUC and British Army were forced to withdraw entirely from some nationalist areas of Belfast. The IRA’s involvement in the clashes was its last major action during its 27-year campaign. It declared its last ceasefire on 19 July.

Wikipedia – 1997 Nationalist Riots in Northern Ireland

This IRA ceasefire helped pave the way to the Good Friday Agreement in April 1998.

Ric Garrido, writer and owner of Loyalty Traveler, shares news and views on hotels, hotel loyalty programs and vacation destinations for frequent guests.

Follow Loyalty Traveler on Twitter and Facebook and RSS feed or subscribe to a daily email newsletter on the upper left side of this page.

1 Comment

Comments are closed.